Cleopatra is certainly an odd presence in my list of book titles. Normally, I have been writing about great men and women of the Christian church. So, why Cleopatra? It all goes back to the beginning of 2016.

Cleopatra is certainly an odd presence in my list of book titles. Normally, I have been writing about great men and women of the Christian church. So, why Cleopatra? It all goes back to the beginning of 2016.

Having thoroughly enjoyed writing about Michelangelo for Chicago Review Press, I decided to embark on a new project for them. Ideas flew back and forth. Most of the titles I suggested were rejected. The main characters from the times and place I know best – Medieval and Renaissance Europe – had been covered, and books on obscure characters don’t seem to sell, at least in the children’s market.

I presented ideas about ancient Rome and Greece. I was brought up, after all, in Italy, where I received a classical education. I studied Latin and Greek, even if I regretfully have lost much of that knowledge as years went by.

As a teenager, I had a crush on Julius Caesar. It might sound strange, especially since my admiration for Caesar soared as I read his Gallic Wars – an odd choice for a 14-year old girl. On the other hand, he had all the marks of a great hero: a genius at war, he was brave, decisive, and mostly clement with his defeated enemies. I never paused to consider the millions of Gauls he killed and enslaved. In fact, I don’t think I ever read about it.

But Caesar didn’t make the cut as a choice for a title, and neither did Alexander. Instead, my editor suggested ancient Egypt – a subject that has fascinated readers at least since the time of Herodotus. Well, it’s a biblical subject, I thought. It will help children to understand much of the background to the Old Testament.

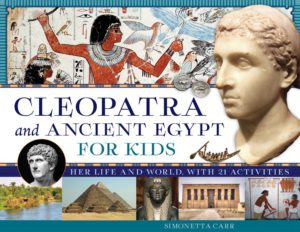

Then my editor refined her suggestion: what about Cleopatra and Ancient Egypt? I didn’t know much about Cleopatra, apart from the common knowledge readily available. Her death marked the end both of the Egyptian kingdom and the Roman Republic, and the beginning of the Roman Empire. I thought it would be interesting to have a look at ancient Egypt from her standpoint – looking back at over 3000 years of history.

I looked at some children’s books on Cleopatra. Most of them gave the same message: she a strong, largely misunderstood leader. Medieval writers portrayed her as a capable queen – in fact, as a scholar and promoter of science! My curiosity was piqued and I signed the contract.

Regrets soon followed. The scarcity of data about Cleopatra has forced biographers and story-tellers to reinvent her story, from the monstruous seductress depicted by Roman writers to the recent rendition of an assertive female leader ahead of her times.

If a definite biography remains impossible to write, rummaging through different versions of her story helped me in other ways and gave me hope that children could find my short book useful.

- It helped me to have a clearer understanding of the pivotal time in which Cleopatra was born.

- It helped me to realize the otherworldly, supernatural nature of Christ’s message. Just thirty years after Cleopatra’s death, Jesus shocked the monotheistic Jews in Herod’s Judea by affirming he was the Son of God. He later shocked his supporters by refusing to use this claim to obtain political power. Instead, he announced the arrival of a spiritual kingdom that would counterintuitively be founded on his death, resurrection and departure from this world. Amazingly, this kingdom of meekness, humility, and admission of spiritual poverty spread like wildfire through apparently weak means: the preaching of Christ’s word and the sacraments. Eventually, it took over the Egyptian population, which became largely Christian until 642 A.D., when it was conquered by Muslim Arabs.

- It helped me to understand how unfounded are the claims that Christianity derives from the Egyptian religion. Those who want to make a parallel between the death of Osiris (who was killed by a jealous brother and patched up by his wife Isis so he could live in the Egyptian afterworld) and the death of Jesus (who gave his life willingly for the sins of the world and defeated death forever by returning in his eternal human body) don’t know much about either Christianity or Egyptian religion.

- It helped me to understand that those who (like Edward Gibbon and other Enlightenment authors) claim that Christianity brought decadence after the highly moral times of Greece and Rome don’t know much about either Christianity or the ancient greco-roman world. (See an excellent article by Tom Holland on this subject: http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/religion/2016/09/tom-holland-why-i-was-wrong-about-christianity)

These realizations came spontaneously while reading the facts with the sincere intent of writing an objective story. I hope my readers will at least reflect on these issues.

You can purchase the book here.

Leave A Comment